Siptah KV 47: The plant

Tomb KV 47, located in the western part of the so-called Eastern Valley, was the last resting place of the second last king of the 19th dynasty named Siptah (1198-1194 BC). It was discovered in 1905 by Edward R. Ayrton and partially cleared of rubble. Then in 1912, Harry Burton cleared the sarcophagus hall; this revealed the large sarcophagus. The tomb has remained in this condition until now, with several corridors and rooms totaling 100 m in length (Fig. 2).

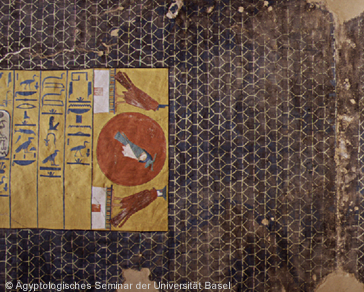

In corridors B and C, the decoration is almost completely preserved and particularly fresh in color, as shown in Fig. 3 with Pharaoh Siptah in front of the falcon-headed sun god Re-Harachte.

From corridor D on, the majority of the wall decoration is destroyed (Fig. 4).

In the lower part of the tomb (corridors G and H, vestibule I and room J1) the ceilings are broken out in the shape of a vault (Fig. 5 with designation of the original ceiling height).

The unusual length of the second part of the tomb is not only caused by the presence of two corridors in the lower part of the tomb - this also occurs in other Ramesside tombs - but mainly by an additional room. Those who are familiar with Ramesside royal tombs expect to enter the sarcophagus hall after corridor H and an anteroom I. However, this is followed by an elongated room. However, an elongated room follows, which is somewhat wider than the corridors and is dominated by a hole in the left wall at a height of about 2 m (Fig. 6). This forms an opening to the tomb KV 32. During the construction of the tomb of Siptah the already existing tomb KV 32 was cut. The undecorated tomb KV 32, which so far could not be attributed to any owner, can be assigned by our excavations to a queen of the 18th Dynasty: the wife of Amenophis II, Tiaa. This planning error resulted in the unforeseen room J1, where the wide sarcophagus hall was supposed to be built. This was built behind it, but could not be finished in time before the death of Siptah.

Room J1 shows remains of decoration. They were partially covered by sticking debris which had to be removed first. It is the sixth and seventh sections of the Underworld Book of Amduat. Fig. 7 shows the condition after cleaning and consolidation of the walls.

The sarcophagus hall (J2) remained unfinished. The rear row of pillars is missing. Only the front row of four pillars, the wall benches on three sides and the ceiling vault in the transverse axis are finished. However, the four existing piers are only in remnants.

The sarcophagus hall is dominated by the monumental granite sarcophagus. The tub is decorated with scenes related to the so-called Book of the Earth. On the top of the lid lies the semi-plastic figure of King Siptah, protected on either side by the goddesses Isis and Nephthys.

In spring 2004, the modern floor in the lower part of the tomb was temporarily removed in order to remove the remaining rubble and complete the documentation. This revealed further objects of Siptah's tomb furnishings, including several small fragments of the granite sarcophagus (Fig. 8).

During the 2001/2002 campaign, the excavation of the rubble outside the tomb, deposited opposite the entrance, was started (Fig. 9). The height of the rubble layer was up to 5 m in this area. Sparse remains of a 19th Dynasty workers' camp were discovered here. Cf. workers' huts.

In 2004/05 an area outside the tomb, east of the entrance, was excavated to a depth of about 3 m down to the bedrock. Besides much pottery, fragments of sarcophagi were found, whose origin is still unclear, as well as objects belonging to the burial equipment of Tiaas (see below) and Siptah.

Already at the time of the discovery of the tomb, remains of the royal burial equipment were found in the rubble, including numerous whole or fragmentary ushabti as well as a number of jar lids, the majority of which are now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art New York. The MISR excavations, both in the tomb and in the outer area, added other comparable objects. Some of the objects found could be reassembled from pieces found in quite different places, as the example of a particularly beautiful and large calcite-alabaster ueshabti of King Siptah shows (Fig. 10).

To the decoration program

Not only the location and architectural planning of a royal tomb followed a carefully elaborated concept, but also the selection and location of the individual decorative elements. The royal ideas of the afterlife and their symbolic design are reflected in the tomb.

In addition to royal underworld texts, various scenes of the gods appear, as well as excerpts from the Book of the Dead, as the case may be. The decoration of the tomb of Siptah is accordingly divided into the following elements:

- Gods scenes: Architrave scene above the entrance (Fig. 11), Maat scenes in the doorways from corridor A to B and C to D (Fig. 12), king in front of Re-Harach in corridor B left(Fig. 3) with following opening scene of the litany of the sun, striding figures in chess room E, Osiris shrine above the exit from the 1st pillar hall.

- Underworld texts: Excerpts from the Litany of the Sun in corridor B and C, excerpts of the 1st to 3rd hour of the Amduat in corridor C and - very fragmentary - of the 4th and 5th hour of the Amduat in corridor D, fragments of the 6th and 7th hrs. of the Amduat in the last corridor before the sarcophagus hall (J1), gate book to be opened (probably 5th and 6th hour) with remains of the Osiris shrine and a fragment of the sand strip as upper wall boundary in the 1st pillar hall.

- Book of the Dead: Saying 151 in duplicate at the end of corridor C.

In addition, there are lines of titulature (on door jambs, reveals, and ceiling in Corridor B), ceiling decorations (winged creatures in Corridor B [Fig. 11], sun litany texts in Corridor C, remains of a star ceiling in Corridor D), and representations of the winged sun above doorways. All these decorative elements have a concrete relation to their place of installation in the tomb. In general, it can be said that the royal tomb complex of the New Kingdom, through its architecture, lettering and imagery, stands for the realms of the underworld which, by analogy with the daily course of the sun, must be traversed cyclically. The course of the sun and thus the nocturnal fate of the sun god are made visible here architecturally and iconographically. Like a clock carved in imperishable stone, the twelve hours of the night unroll, but in a counterclockwise direction, so to speak, in that the aged sun god (at the setting in the west) is rejuvenated in the course of the night and is reborn in the morning (at the rising in the east) with renewed strength. Through the connection of the deceased king with the sun god, the latter is taken into the eternal cycle according to the omnipresent model of nature, while at the same time the ancient topos of the dead who has become Osiris and is posthumously revived is also present.

These two fundamental ideas of the afterlife form the most important basis for the motifs of tomb decoration. In the intended unification of Re and Osiris, analogous to the nightly union of the free-moving Ba and the rigid corpse hoped for also by private individuals, for example in the Book of the Dead, the solar aspect of renewal is combined with the Osirian aspect of protection and revival.

By decorating the tomb with the appropriate texts from the various underworld books, the king is given the necessary stock of knowledge (about the ways, sites, gates, names, demons, sayings, etc.) that make him an Ach-iqer, i.e., an aptly endowed ancestor spirit, and at the same time magically foreshadows the positive outcome of the nocturnal regeneration through the placement in text and image.

In addition to the royal underworld texts (Litany of the Sun, Amduat, Book of Gates), a whole series of other pictorial motifs appear that show the king in contact with the world of the gods. The pharaoh appears before the various deities and receives protection and life, and in turn presents gifts to the gods. Through this dialogue, the deceased king is finally accepted into the community of the gods.

The corresponding scenes in Siptah show that even before his actual entry into the tomb the king worships the sun god in his various manifestations (architrave scene), in whose eternal cyclic course he wants to be involved, while at the same time the two goddesses Isis and Nephthys allude to the hoped-for Osiris becoming.

On entering the kingdom beyond, he is received by Re-Harach at the entrance of the tomb as king of both halves of the country and under the protection of the daughter of Re (Maat on the heraldic plants, fig. 10), who at the same time guarantees the continuity of the world order, and is presented with various promises (entrance scene). Winged creatures with the heads of the crown goddesses Nechbet (vulture) and Wadjit (snake) flutter above him - as they do above the central axis of temples - and accompany him into the tomb (fig. 11), while the texts and depictions on the walls and ceiling equate him with Re and integrate him into the daily course of the sun (litany of the sun, amduat).

Finally, the first part of his journey ends with the successful embalming and equipping with the necessary rites and utensils by Anubis (Book of the Dead, Spell 151, Fig. 12) at the end of Corridor C and entering the realm of Sokar in Corridor D before the king reaches the burial place of Sokar with the Chess Room, still surrounded and guarded by protective deities (Chess Room). And finally, in the upper pillared hall, he assumes the appearance of Osiris, as expressed in the scene on the back wall above the exit to Corridor G (Osiris Shrine).

From then on he continues his journey no longer as king but as god. This creates, as it were, a caesura of the tomb floor plan into an upper and a lower half. In the lower part of the tomb, which was completely decorated with Siptah contrary to previous statements, he continues his underworldly journey (Amduat). Before the final burial and the associated successful rejuvenation in the sarcophagus hall the still existing traces at the end of the last corridor with the 6th (left) and 7th (right) hour of the Amduat point to the union of Ba and corpse as well as the overcoming of Apophis.

Finally, the king (and thus the sun god) rests at the end of his passage through the royal tomb in his sarcophagus, surrounded by texts and representations of the course of the sun, while in the representation on the lid at the same time his becoming Osiris is again clarified.

To the sun litany

The sun litany placed in the corridors B and C is a long hymn to the sun god. It belongs to the standard decoration of the Ramesside royal tombs (19th and 20th Dynasty). Using the specific example of the record in Siptah's tomb, the text was attempted to be understood as a liturgical text, a text that was recited in the tomb by priests. For the question of how the individual sections, which also contain images, relate to each other, new insights could be gained on the basis of the recording in the room. Thus, the text section that is always placed on the ceiling in the third corridor can be interpreted as a refain to the long litany of invocations to the sun god that form the beginning of the composition.

The Reign of Siptah

The circumstances of the accession and reign of Siptah (1196-1190) , who ruled as the 7th king of the 19th dynasty and successor to Sethos II for 5 years and 9 months, cannot yet be determined with complete certainty. He was considered illegitimate to the 20th dynasty. A new interpretation of the historical evidence leads to the following scenario: Towards the end of Sethos II's reign, the king, lacking a son of his own, designated a high court official named Baj (Beja) as heir to the throne. This Baj (Beja) was treasurer of the entire country and, along with Siptah's stepmother, Tausret, was the dominant political figure of the time. A number of monuments attest to Baj alongside Siptah; he had the privilege of his own tomb in the Valley of the Kings (KV 13), a vineyard in the delta, claimed participation in the royal cult of the dead, and even adopted royal epithets and attributes. However, as is evident from the decoration of the barque sanctuary of Sethos II at Karnak, an heir to the throne - a prince Seti-Merenptah - was born to Sethos II shortly before his death or posthumously after all, apparently by his consort (and later queen) Tausret. Baj (Beja) raised in this situation the underage prince Siptah, perhaps son of king Merenptah by a Syrian concubine, to king, but may have acted behind him as actual regent. According to his mummy, Siptah died at about 20 years of age, so he was only 14 years old at the time of his accession. In addition, his mummy shows a pathological curvature of the left foot, which presumably originates from a disease of poliomyelitis (infantile paralysis) (Fig. 13).

In the great papyrus Harris, an account of Ramses IV, Siptah is retrospectively referred to as "he who reigned six years, a Syrian". Probably as a reaction to the existence of the heir to the throne Seti-Merenptah, Siptah changed his titulature. The proper name Rameses-Siptah and the throne name The One Enthroned by Re, Beloved of Amun were now replaced by the proper name Merenptah-Siptah and the throne name Useful to Re, whom Re chose . After the early death of the potential heir to the throne Seti-Merenptah, who may have been buried in the "gold tomb" KV 56 in the Valley of the Kings, the conflict for the throne between Baj (Beja) and Siptah seems to have escalated in the fourth year of Siptah: With the unexpected death of Sethos II's natural son, who had once preceded Beja as crown prince, Beja was able to reassert his claim to the throne (designation by Sethos II) over that of Siptah, and indeed a political conflict between the two is evident in the sources. After the death of her own son, however, Tausret now sided with Siptah as co-ruler. In the 5th year of his reign, as we know from a newly discovered ostracon, Siptah had the disloyal Baj (Beja) executed as an enemy of the state. But Siptah himself survived him only less than one year, and also Tausret could hold as the sole queen of Egypt only one and a half year, until Sethnacht founded the 20th dynasty.

Siptah is attested mainly by inscriptions and representations in Wadi Halfa and Abu Simbel (installation of the viceroy of Kush, Sethi, in his 1st year) as well as in Sehel, Amada, Aswan and Gebel es-Silsileh. Construction of the royal tomb (KV 47) is begun in his 1st year; the cartouches were erased for an unknown reason (attempted usurpation of the tomb by Baj?) and later restored. The coffin and mummy of Siptah were moved to the tomb of Amenophis II in the 21st Dynasty. The founding deposits of his mortuary temple, which apparently did not get beyond beginnings, contained plaques of faience, gold and silver plate, scarabs, rings, etc., among them objects (also wine jar inscriptions) of the chancellor Baj. In addition to his tomb and funerary temple, there is a statue in Munich that shows Siptah on the lap of a worn-out figure, which has apparently fallen into disrepute and in which Baj (Beja) can probably be recognized.

Publications on this topic

- T. Schneider, Siptah and Beja. Reassessment of a historical constellation, in: Zeitschrift für ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde [ZÄS], vol. 130, 2003, 134-146.

- D. Cilli, Delivery Ostraca Discovered Adjacent to KV 47, in: Mark Collier / Steven Snape (eds), Ramesside Studies in Honour of K. A. Kitchen, Bolton 2011, 95-110.

- H. Jenni, Sonnenlitanei, in: Bernd Janowski / Daniel Schwemer (eds.), Grab-, Sarg-, Bau- und Votivinschriften (Texte aus der Umwelt des Alten Testaments. Neue Folge, vol. 6 [TUAT.NF 6]), Gütersloh 2011, 236-272.

- D. Cilli, Die Ostraka der späten 19. Dynastie aus dem Gelände des Grab Pharaos Siptah (KV 47) im Tal der Könige, Dissertation, Basel 2013 (in Italian).

- A. Dorn / E. Paulin-Grothe, Ausgrabungen im Tal der Könige 1998-2008: Grabungsareale und Spuren früherer Ausgräuber, in: Zur modernen Geschichte des Tals der Könige. Conference in Basel, September 1, 2007, with contributions on the tomb of Ramses X. (KV 18) and on finds from modern times, ed. by Hanna Jenni (Aegyptiaca Helvetica [AH] 25), Basel: Schwabe 2015, 66-72.

The tomb of Siptah had long been known in Egyptological literature, but was far from being fully documented. Post-excavations and detailed analyses were necessary to close this gap. In the process, new questions have arisen that are important both for the history of architecture and for the history of funerary texts.

This sub-project was sponsored with a substantial financial contribution from LONGINES.

Quick Links