The Basel ProfileResearch

Research in the field of historical-comparative linguistics

Historical-comparative linguistics of Indo-European languages or Indo-European studies is a comparatively young science. It is only about 200 years old, and its methodology and the discovery of its subject is not older.

This new subject is the so-called Indo-European languages, not only in their individual existence (in this respect many of them have been known for a long time), but above all in their totality as a family of genetically related languages, historically going back to a common basic language.

The methodology is based on the realization that languages do not simply evolve (this was also already known), but evolve in a regular way. This allows to trace languages into their unattested past, i.e. to reconstruct them, especially by historical language comparison within a language family.

Research focus

The subject "Comparative Indo-European Linguistics" was abolished in Basel in 1983 and since then can no longer be studied as a separate subject.

Since then, its teaching focus has been on Greek and Latin, but other Indo-European languages, e.g. Sanskrit, Hittite, Gothic, and the post-ancient linguistic history of Europe are regularly examined.

The most accurate name of the discipline in German is 'Historisch-vergleichende Sprachwissenschaft der indogermanischen Sprachen' (French: Grammaire comparée des langues indo-européennes. English: Comparative Philology. American: Indo-European Studies). This implies, on the one hand, that historical-comparative linguistics can also be carried out in other language families; on the other hand, that the Indo-European languages can also be viewed linguistically in a different way than under the historical-comparative lens.

As far as the first implication is concerned, Indo-European studies has a couple of advantages that make it the most important historical-comparative linguistics:

- Its subject matter is a very 'child-rich' language family, i.e., there are very many daughter languages that are either attested in the past or still alive today (this allows for manifold historical-comparative combinations and particularly well-supported reconstructions).

- The language family is comparatively young (the common basic language dates back only about 6000 years, which makes it easy to prove that the languages involved are really related).

- The basic language is not attested (otherwise we could not or would not have to reconstruct it).

- Some Indo-European languages are among the few languages of mankind that are directly attested over several millennia, and thus their variability can be observed early and over a long period of time (e.g. Greek for almost 3500 years).

- A few Indo-European languages, namely English and Spanish, are very widespread in the world today (therefore potentially a great many people are interested in Indo-European studies, but in real terms only those who are not indifferent to the history of their culture and language).

- Three Indo-European languages, Greek, Latin and Sanskrit, are important so-called 'classical' languages of culture and literature (therefore potentially ...).

As far as the second implication is concerned, the spirit of the times is not very favorable to disciplines like Indo-European studies: Linguistics is currently concerned mainly with language states and language uses, not with language development. This reflects a general tendency in the humanities: The study of topics in which historical consequences or causalities play a role is somewhat out of fashion (exceptions are items with immediate - especially legal, economic, social, or political - implications for the present). In contrast, questions that can be solved by means of cross-sectional representations of the subject matter at a given time and with explanations 'from within' are in vogue; this approach is now being applied not only to topics of the present, but also to those of the past. For historical linguistics, on the other hand, chronology is the be-all and Ω-all.

On the whole, however, Indo-European studies have no reason to despair:

- The texts with which it can deal are usually decidedly valuable. It is not likely that society will afford to give away entirely the enormous knowledge that the small group of specialists in these texts has acquired over the past 200 years and continues to develop today. (The average high quality of the old texts is probably due, among other things, to the fact that before the invention of printing - and even of electronic storage media - the price of a word or text recorded in writing, i.e. handed down or copied, was higher by orders of magnitude than it is today; therefore, almost only good texts were preserved and handed down).

- Two of the classical languages, for whose linguistics the Indo-Germanist is traditionally responsible (because only with the historical-language-comparative research approach a scientifically maximum yield can be achieved), are Latin and Greek. These are for the culture of the West firstly linguistically omnipresent until today (just now: classical, traditional, historical, maximum, culture, omnipresent - and even: science), and secondly many of the texts written in them belong to the best of the world literature, have an effect until today and still deserve intensive scientific (also linguistic) research.

- The third important classical language, Sanskrit, is represented by a fully developed Indology at only a few universities. Where one does not exist, the Indo-Germanist is charged with a minimal teaching load, and where an Indology exists, the Indo-Germanist covers the linguistic side (at least in the area of Vedic and Classical Sanskrit), as with Latin and Greek.

- Also various other subjects can profitably use the assistance of the Indo-Europeanist, especially for their respective older language states (so Germanic studies and theology for Gothic, Slavic studies for Old Church Slavonic, Near Eastern studies and Islamic studies for Old Persian, etc.).

- A significantly larger proportion of the population than one might think is very interested in questions such as 'Where does this word come from?', 'What does this word actually mean?', 'How and when did this word come into being?' Here, in the field of so-called etymology, the Indo-Europeanist can help best and most completely.

In view of this variety of tasks, no one will be able to deny Indo-European studies its right to exist with convincing arguments in the future. However, as in the other historical sciences, it will take a fair amount of perseverance and persuasion in the near future to make and keep clear to our present society the usefulness of the sciences that process and convey their cultural sources to it.

(Additional information on these questions can be found in the text"Orchid Indo-Germanic Studies").

Indo-European studies deals in principle with all aspects of the languages it investigates. However, it follows from the fact that many of the language states it studies are now extinct that certain aspects can no longer be studied for lack of evidence. For example, it is not possible to do dialect geography of Gothic, to describe Hittite by means of modern phonetic devices, or to analyze Vedic Sanskrit according to criteria of sociolinguistics. The use of generative grammar is also of limited interest for most languages of importance to Indo-European studies.

The most important subfields of Indo-European studies are:

- Phonology: here it is determined as precisely as possible how many different sounds (phonemes) each language had at certain times, how these were pronounced (approximately) - depending on the phonetic environment - and how they developed (in these environments) before and after. Reconstructive attempts are made to determine the Urindogermanic phonetic system and in turn to trace it into the past.

- Word formation and etymology: This subdiscipline investigates the vocabulary. This includes, on the one hand, the description of the living (productive) word-forming means with which new words were formed in the individual languages at certain times according to certain patterns, and on the other hand, the explanation of the inherited words, the reconstruction of the vocabulary of the basic language and the determination and description of the word-forming means which were productive at that time. This reconstruction is important with regard to the basic language morphology and its single language development.

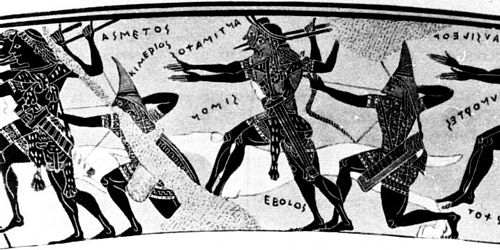

- Morphology: The older Indo-European languages are strongly inflectional (some of them still are, e.g. Greek and the Baltic-Slavic languages as well as - but only for the verb - the Romance languages). Morphology describes the forms and their functions, as well as their changes, in each language and attempts to reconstruct the Uridgian form system.

- Syntax: The single-language description of syntax includes the description of the functions and usages of the morphosyntactic (i.e., expressed by inflection of words) categories, the sentence structure and the conjunctions used for it, etc., as well as word order. As far as reconstruction is concerned, we can say much in the first area, some in the second, and little in the third. Nevertheless, an essential principle of word order, the enclisis, has been shown on the basis of the Idg. languages and has also been demonstrated for the Uridg. basic language (n.b. by Jacob Wackernagel).

- Stylistics: This field includes the studies on the Indo-European poetic language, in which it is proved (partly also with metrical arguments) that certain poetic expressions go back to the basic language.

- Culture reconstruction: Here it is a question of inferring from the vocabulary reconstructed for the basic language general and special characteristics of the culture of the speaker community of the Uridg. basic language. This is also connected to the (unresolved) question of the so-called 'original homeland of the Indo-Europeans'.

The following main groups can be distinguished:

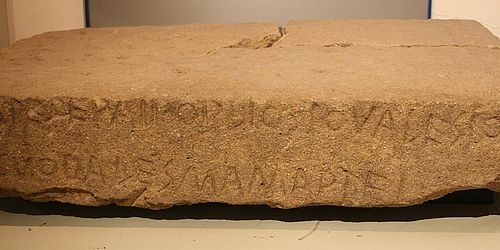

- Anatolian languages (extinct) with Hittite as the most important language (texts before 1200 BC, in Sumerian-Babylonian cuneiform).

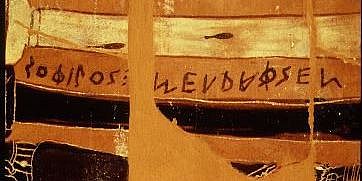

- Greek with first texts (in 'Mycenaean' dialect, written in 'Linear B') from before 1200 BC; after an interruption attested again since ca. 750 BC, in 'Alphabet'.

- Indo-Iranian with Old Indian (first Vedic, from c. 1000 B.C., then Sanskrit, in 'Devanāgarī') and Old Iranian (Avestic from c. 600 B.C. [?], written down much later in its own phonetic script; Old Persian c.a. c. 520 B.C., in a special cuneiform script c.a. on rock and stone blocks).

- Italic languages, attested from the 7th century B.C., with Latin (and its Romance daughters) the main representative, written with a more developed alphabet.

- Celtic, with little evidence from ancient Gaul, then mainly Old, Middle, and New Irish (Gaelic), almost all written in alphabets.

- Germanic, first well attested by Gothic (Bible translation from the middle of the 4th century AD, in an alphabet specially derived from Greek), later in a southern (mainly German and English) and a northern (Nordic) group (mainly in the Latin alphabet).

- Slavonic, attested from the 9th century (Old Church Slavonic), later in three groups (Eastern, Southern and Western Slavonic), mostly in the Cyrillic and Latin alphabets.

- Baltic, attested from the 16th century (today Lithuanian and Latvian), mostly in the Latin alphabet. In addition, there are three individual languages, which embody independent subgroups:

- Armenian, from the 5th century onward (classical high language, in its own alphabet)

- Tocharian (extinct), attested in the 7th/8th century AD on the Tarim River in East Turkestan (now part of China), in a script derived from Indian.

- Albanian, attested since the 15th/16th century, in the Latin alphabet, formerly also in the Cyrillic, Greek, and Arabic alphabets.

- Phrygian, attested from the 8th c. BC to the 3rd c. AD in Central Anatolia, in texts written partly in the Phrygian alphabet and partly with Greek letters.

Quick Links